[Live Lab] Streaming 101: Hands-On with Kafka & Flink | Secure Your Spot

Apache Kafka, Samza, and the Unix Philosophy of Distributed Data

One of the things I realised while doing research for my book is that contemporary software engineering still has a lot to learn from the 1970s. As we’re in such a fast-moving field, we often have a tendency of dismissing older ideas as irrelevant – and consequently, we end up having to learn the same lessons over and over again, the hard way. Although computers have got faster, data has got bigger and requirements have become more complex, many old ideas are actually still highly relevant today. In this blog post I’d like to highlight one particular set of old ideas that I think deserves more attention today: the Unix philosophy. I’ll show how this philosophy is very different from the design approach of mainstream databases, and explore what it would look like if modern distributed data systems learnt a thing or two from Unix.

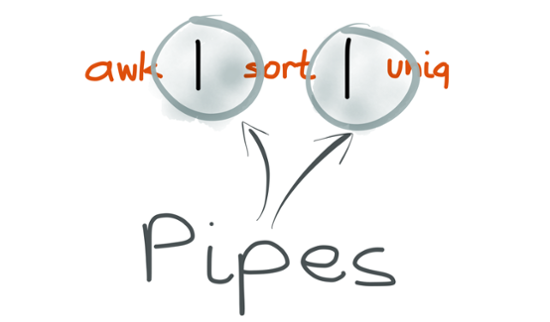

In particular, I’m going to argue that there are a lot of similarities between Unix pipes and Apache Kafka, and that this similarity enables good architectural styles for large-scale applications. But before we get into that, let me remind you of the foundations of the Unix philosophy. You’ve probably seen the power of Unix tools before – but to get started, let me give you a concrete example that we can talk about. Say you have a web server that writes an entry to a log file every time it serves a request. For example, using the nginx default access log format, one line of the log might look like this:

216.58.210.78 - - [27/Feb/2015:17:55:11 +0000] "GET /css/typography.css HTTP/1.1"

200 3377 "http://martin.kleppmann.com/" "Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X

10_9_5) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/40.0.2214.115 Safari/537.36"

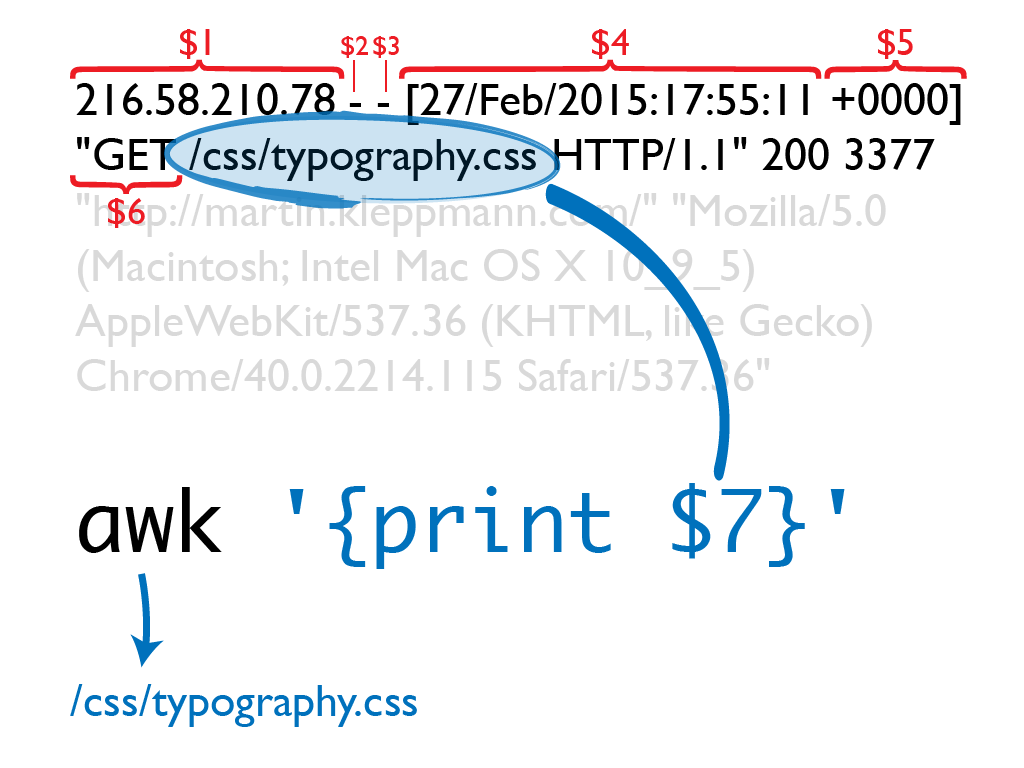

(That is actually one line, it’s only broken up into multiple lines here for readability.) This line of the log indicates that on 27 February 2015 at 17:55:11 UTC, the server received a request for the file /css/typography.css from the client IP address 216.58.210.78. It then goes on to note various other details, including the browser’s user-agent string. Various tools can take these log files and produce pretty reports about your website traffic, but for the sake of the exercise, let’s build our own, using basic Unix tools. Let’s determine the 5 most popular URLs on our website. To start with, we need to extract the path of the URL that was requested, for which we can use awk. awk doesn’t know about the format of nginx logs – it just treats the log file as text. By default, awk takes one line of input at a time, splits it by whitespace, and makes the whitespace-separated components available as variables $1, $2, etc. In the nginx log example, the requested URL path is the seventh whitespace-separated component: Now that you’ve extracted the path, you can determine the 5 most popular pages on your website as follows:

Now that you’ve extracted the path, you can determine the 5 most popular pages on your website as follows:

The output of that series of commands looks something like this:

4189 /favicon.ico

3631 /2013/05/24/improving-security-of-ssh-private-keys.html

2124 /2012/12/05/schema-evolution-in-avro-protocol-buffers-thrift.html

1369 /

915 /css/typography.css

Although the above command line looks a bit obscure if you’re unfamiliar with Unix tools, it is incredibly powerful. It will process gigabytes of log files in a matter of seconds, and you can easily modify the analysis to suit your needs. For example, if you want to count top client IP addresses instead of top pages, change the awk argument to '{print $1}'. Many data analyses can be done in a few minutes using some combination of awk, sed, grep, sort, uniq and xargs, and they perform surprisingly well. This is no coincidence: it is a direct result of the design philosophy of Unix.

Although the above command line looks a bit obscure if you’re unfamiliar with Unix tools, it is incredibly powerful. It will process gigabytes of log files in a matter of seconds, and you can easily modify the analysis to suit your needs. For example, if you want to count top client IP addresses instead of top pages, change the awk argument to '{print $1}'. Many data analyses can be done in a few minutes using some combination of awk, sed, grep, sort, uniq and xargs, and they perform surprisingly well. This is no coincidence: it is a direct result of the design philosophy of Unix.

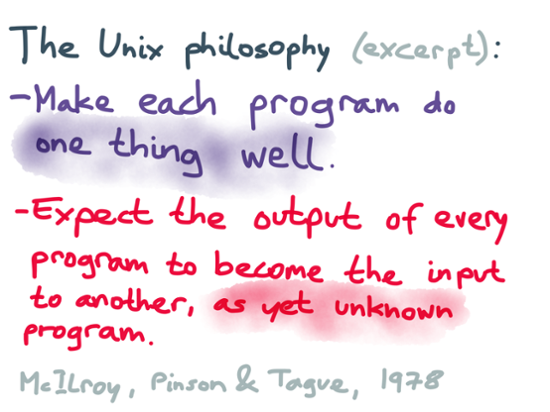

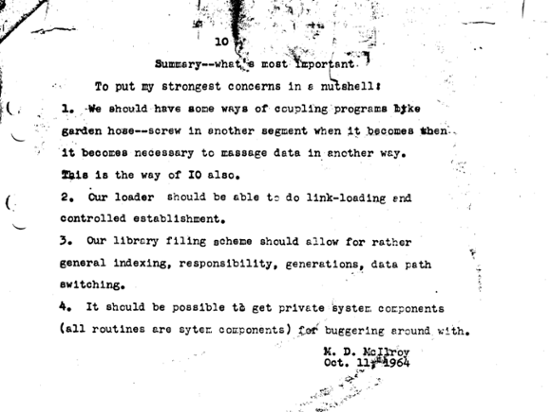

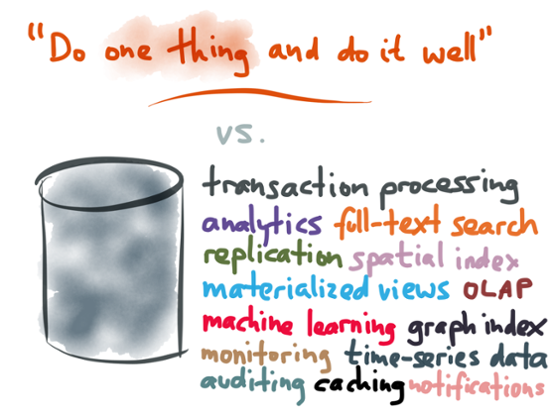

The Unix philosophy is a set of principles that emerged gradually during the design and implementation of Unix systems during the late 1960s and ’70s. There are various interpretations of the Unix philosophy, but two points that particularly stand out were described by Doug McIlroy, Elliot Pinson and Berk Tague as follows in 1978:

- Make each program do one thing well. To do a new job, build afresh rather than complicate old programs by adding new “features.”

- Expect the output of every program to become the input to another, as yet unknown, program.

These principles are the foundation for chaining together programs into pipelines that can accomplish complex processing tasks. The key idea here is that a program does not know or care where its input is coming from, or where its output is going to: it may be a file, or another program that’s part of the operating system, or another program written by someone else entirely.

The tools that come with the operating system are generic, but they are designed such that they can be composed together into larger programs that can perform application-specific tasks. The benefits that the designers of Unix derived from this design approach sound quite like the ideas of the Agile and DevOps movements that appeared decades later: scripting and automation, rapid prototyping, incremental iteration, being friendly to experimentation, and breaking down large projects into manageable chunks. Plus ça change.

When you join two commands with the pipe character in your shell, the shell starts both programs at the same time, and attaches the output of the first process to the second process’ input. This attachment mechanism uses the pipe syscall provided by the operating system. Note that this wiring is not done by the programs themselves, but by the shell – this allows them to be loosely coupled, and not worry about where their input is coming from, or where their output is going.

The pipe had been invented in 1964 by Doug McIlroy, who first described it like this in an internal Bell Labs memo: “We should have some ways of connecting programs like [a] garden hose – screw in another segment when it becomes necessary to massage data in another way.” Dennis Richie later wrote up his perspective on the memo.

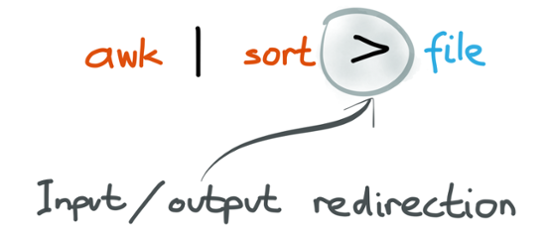

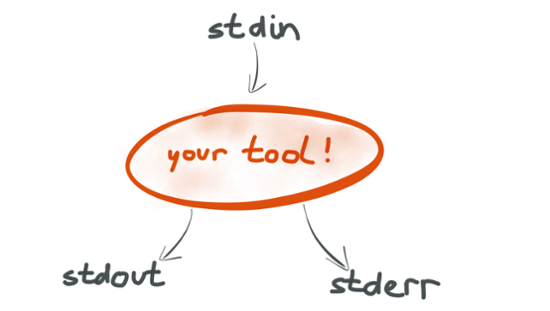

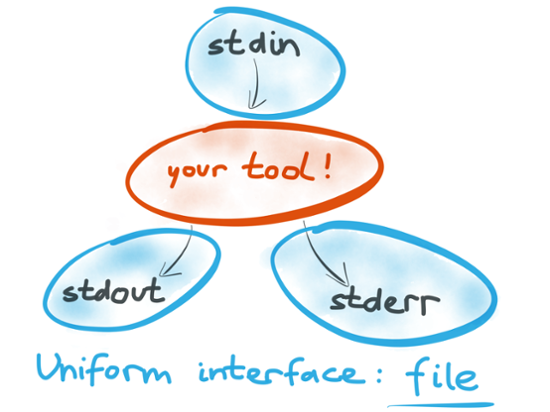

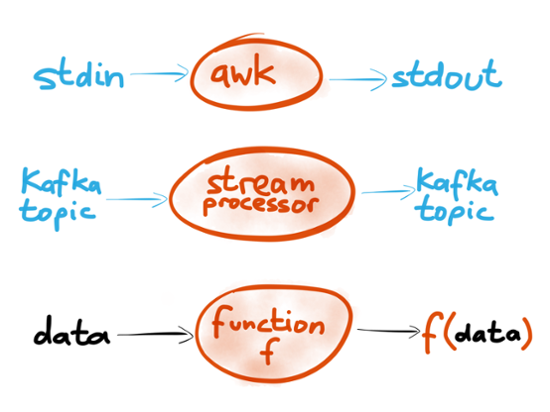

They also realised early that the inter-process communication mechanism (pipes) can look very similar to the mechanism for reading and writing files. We now call this input redirection (using the contents of a file as input to a process) and output redirection (writing the output of a process to a file). The reason that Unix programs can be composed so flexibly is that they all conform to the same interface: most programs have one stream for input data (stdin) and two output streams (stdout for regular output data, and stderr for errors and diagnostic messages).

Programs may also do other things besides reading stdin and writing stdout, such as reading and writing files, communicating over the network, or drawing a graphical user interface. However, the stdin/stdout communication is considered to be the main way how data flows from one Unix tool to another. And the great thing about the stdin/stdout interface is that anyone can implement it easily, in any programming language. You can develop your own tool that conforms to this interface, and it will play nicely with all the standard tools that ship as part of the operating system.

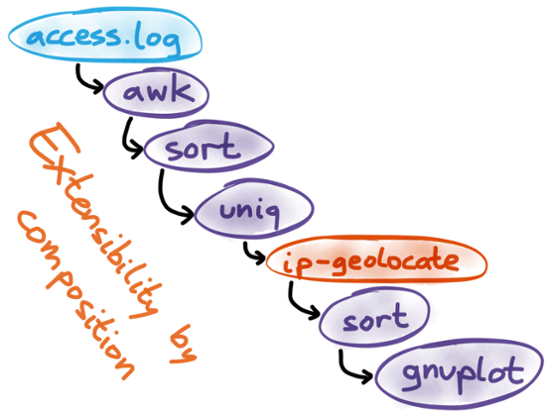

For example, when analysing a web server log file, perhaps you want to find out how many visitors you have from each country. The log doesn’t tell you the country, but it does tell you the IP address, which you can translate into a country using an IP geolocation database. Such a database isn’t included with your operating system by default, but you can write your own tool that takes IP addresses on stdin and outputs country codes on stdout. Once you’ve written that tool, you can include it in the data processing pipeline we discussed previously, and it will work just fine. This may seem painfully obvious if you’ve been working with Unix for a while, but I’d like to emphasise how remarkable this is: your own code runs on equal terms with the tools provided by the operating system. Apps with graphical user interfaces or web apps cannot simply be extended and wired together like this. You can’t just pipe Gmail into a separate search engine app, and post results to a wiki. Today it’s an exception, not the norm, to have programs that work together as smoothly as Unix tools do.

Change of scene. Around the same time as Unix was being developed, the relational data model was proposed, which in time became SQL, and was implemented in many popular databases. Many databases actually run on Unix systems. Does that mean they also follow the Unix philosophy?

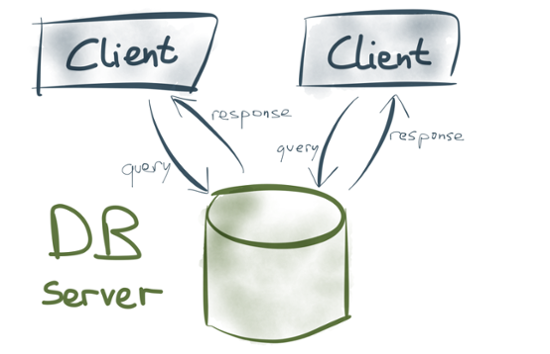

The dataflow in most database systems is very different from Unix tools. Rather than using stdin and stdout as communication channels, there is a database server, and several clients. The clients send queries to read or write data on the server, the server handles the queries and sends responses to the clients. This relationship is fundamentally asymmetric: clients and servers are distinct roles.

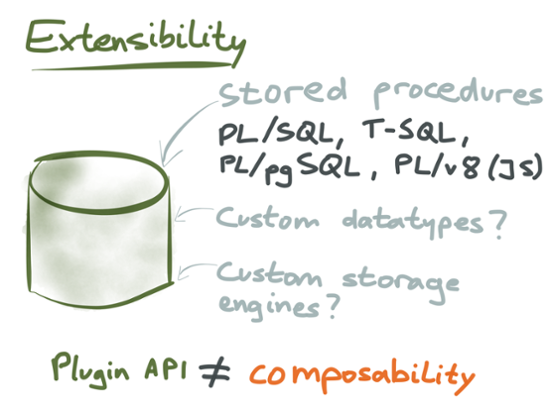

What about the composability and extensibility that we find in Unix systems? Clients can do anything they like (since they are application code), but database servers are mostly in the business of storing and retrieving your data. Letting you run arbitrary code is not their top priority. That said, many databases do provide some ways of extending the database server with your own code. For example, many relational databases let you write stored procedures in their own, rudimentary procedural language such as PL/SQL (and some let you run code in a general-purpose programming language such as JavaScript). However, the things you can do in stored procedures are limited. Other extension points in some databases are support for custom data types (this was one of the early design goals of Postgres), or pluggable storage engines. Essentially, these are plugin APIs: you can run your code in the database server, provided that your module adheres to a plugin API exposed by the database server for a particular purpose. This kind of extensibility is not the same as the arbitrary composability we saw with Unix tools. The plugin API is totally controlled by the database server, and subordinate to it. Your extension code is a guest in the database server’s home, not an equal partner.

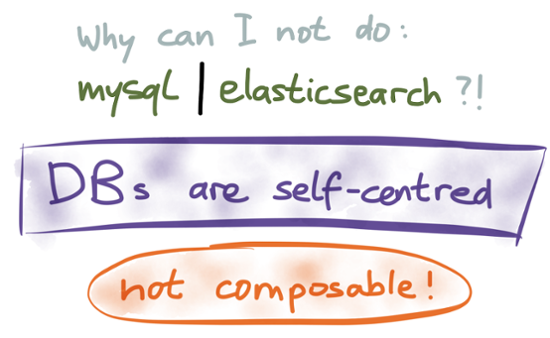

A consequence of this design is that you can’t just pipe one database into another, even if they have the same data model. Nor can you insert your own code into the database’s internal processing pipelines (unless the server has specifically provided an extension point for you, such as triggers). I feel the design of databases is very self-centered. A database seems to assume that it’s the centre of your universe: the only place where you might want to store and query your data, the source of truth, and the destination for all queries. The closest you can get to piping data in and out of it is through bulk-loading and bulk-dumping (backup) operations, but those operations don’t really use any of the database’s features, such as query planning and indexes. If a database was designed according to the Unix philosophy, it would be based on a small number of core primitives that you could easily combine, extend and replace at will. Instead, databases are tremendously complicated, monolithic beasts. While Unix acknowledges that the operating system will never do everything you might want, and thus encourages you to extend it, databases try to implement all the features you may need in a single program.

Perhaps that design is fine in simple applications where a single database is indeed sufficient. However, many complex applications find that they have to use their data in various different ways: they need fast random access for OLTP, big sequential scans for analytics, inverted indexes for full-text search, graph indexes for connected data, machine learning systems for recommendation engines, a push mechanism for notifications, various different cached representations of the data for fast reads, and so on. A general-purpose database may try to do all of those things in one product (“one size fits all”), but in all likelihood it will not perform as well as a tool that is specialized for one particular purpose. In practice, you can often get the best results by combining various different data storage and indexing systems: for example, you may take the same data and store it in a relational database for random access, in Elasticsearch for full-text search, in a columnar format in Hadoop for analytics, and cached in a denormalized form in memcached. When you need to integrate different databases, the lack of Unix-style composability is a severe limitation. (I’ve done some work on piping data out of Postgres into other applications, but there’s still a long way to go before we can simply pipe any database into any other database.)

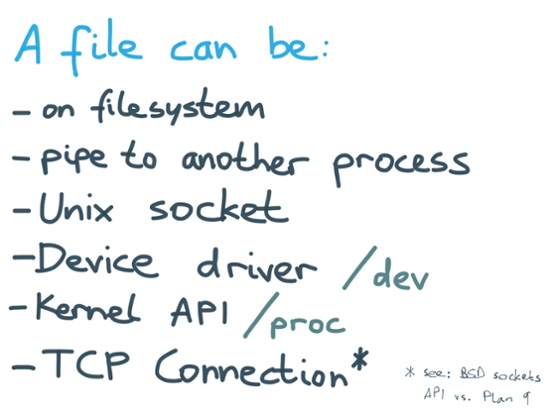

We said that Unix tools are composable because they all implement the same interface of stdin, stdout and stderr – and each of these is a file descriptor, i.e. a stream of bytes that you can read or write like a file. This interface is simple enough that anyone can easily implement it, but it is also powerful enough that you can use it for anything. Because all Unix tools implement the same interface, we call it a uniform interface. That’s why you can pipe the output of gunzip to wc without a second thought, even though the authors of those two tools probably never spoke to each other. It’s like lego bricks, which all implement the same pattern of knobbly bits and grooves, allowing you to stack any lego brick on any other, regardless of their shape, size or colour.

The uniform interface of file descriptors in Unix doesn’t just apply to the input and output of processes, but it’s a very broadly applied pattern. If you open a file on the filesystem, you get a file descriptor. Pipes and unix sockets provide file descriptors that are a communication channel to another process on the same machine. On Linux, the virtual files in /dev are the interfaces of device drivers, so you might be talking to a USB port or even a GPU. The virtual files in /proc are an API for the kernel, but since they’re exposed as files, you can access them with the same tools as regular files. Even a TCP connection to a process on another machine is a file descriptor, although the BSD sockets API (which is most commonly used to establish TCP connections) is arguably not as Unixy as it could be. Plan 9 shows that even the network could have been cleanly integrated into the same uniform interface. To a first approximation, everything on Unix is a file. This uniformity means the logic of Unix tools is separated from the wiring, making it more composable. sed doesn’t need to care whether it’s talking to a pipe to another process, or a socket, or a device driver, or a real file on the filesystem. It’s all the same.

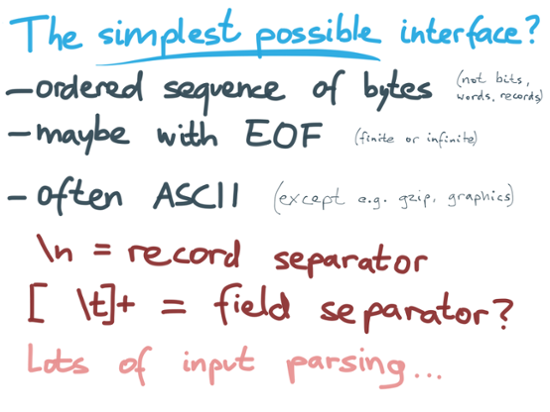

A file is a stream of bytes, perhaps with an end-of-file (EOF) marker at some point, indicating that the stream has ended (a stream can be of arbitrary length, and a process may not know in advance how long its input is going to be). A few tools (e.g. gzip) operate purely on byte streams, and don’t care about the structure of the data. But most tools need to parse their input in order to do anything useful with it. For this, most Unix tools use ASCII, with each record on one line, and fields separated by tabs or spaces, or maybe commas. Files are totally obvious to us today, which shows that a byte stream turned out to be a good uniform interface. However, the implementors of Unix could have decided to do it very differently. For example, it could have been a function callback interface, using a schema to pass records from process to process. Or it could have been shared memory (like System V IPC or mmap, which came along later). Or it could have been a bit stream rather than a byte stream. In a sense, a byte stream is a lowest common denominator – the simplest possible interface. Everything can be expressed in terms of a stream of bytes, and it’s fairly agnostic to the transport medium (pipe from another process, file on disk, TCP connection, tape, etc). But this is also a disadvantage, as we shall discuss later.

We’ve seen that Unix developed some very good design principles for software development, and that databases have taken a very different route. I would love to see a future in which we can learn from both paths of development, and combine the best ideas from each. How can we make 21st-century data systems better by learning from the Unix philosophy? In the rest of this post I’d like to explore what it might look like if we bring the Unix philosophy to the world of databases.

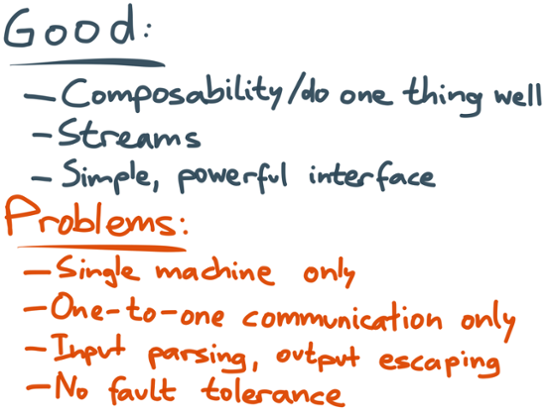

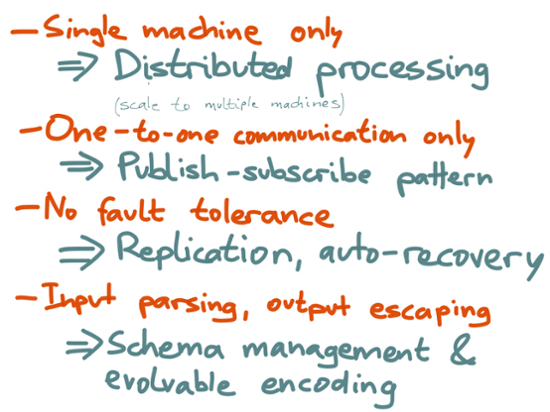

First, let’s acknowledge that Unix is not perfect. Although I think the simple, uniform interface of byte streams was very successful at enabling an ecosystem of flexible, composable, powerful tools, Unix has some limitations:

- It’s designed for use on a single machine. As our applications get every more data and traffic, and have higher uptime requirements, moving to distributed systems is becoming increasingly inevitable. Although a TCP connection can be made to look somewhat like a file, I don’t think that’s the right answer: it only works if both sides of the connection are up, and it has somewhat messy edge case semantics. TCP is good, but by itself it’s too low-level to serve as a distributed pipe implementation.

- A Unix pipe is designed to have a single sender process, and a single recipient. You can’t use pipes to send output to several processes, or to collect input from several processes. (You can branch a pipeline with tee, but a pipe itself is always one-to-one.)

- ASCII text (or rather, UTF-8) is great for making data easily explorable, but it quickly gets messy. Every process needs to be set up with its own input parsing: first breaking the byte stream into records (usually separated by newline, though some advocate 0x1e, the ASCII record separator). Then a record needs to be broken up into fields, like the $7 in the awk example at the beginning. Separator characters that appear in the data need to be escaped somehow. Even a fairly simple tool like xargs has about half a dozen command-line options to specify how its input should be parsed. Text-based interfaces work tolerably well, but in retrospect, I am pretty sure that a richer data model with explicit schemas would have worked better.

- Unix processes are generally assumed to be fairly short-running. For example, if a process in the middle of a pipeline crashes, there is no way for it to resume processing from its input pipe – the entire pipeline fails and must be re-run from scratch. That’s no problem if the commands run only for a few seconds, but if an application is expected to run continuously for years, better fault tolerance is needed.

I think we can find a solution that overcomes these downsides, while retaining the Unix philosophy’s benefits.

The cool thing is that this solution already exists, and is implemented in Kafka and Samza, two open source projects that work together to provide distributed stream processing. As you probably already know from other posts on this blog, Kafka is a scalable distributed message broker, and Samza is a framework that lets you write code to consume and produce data streams.

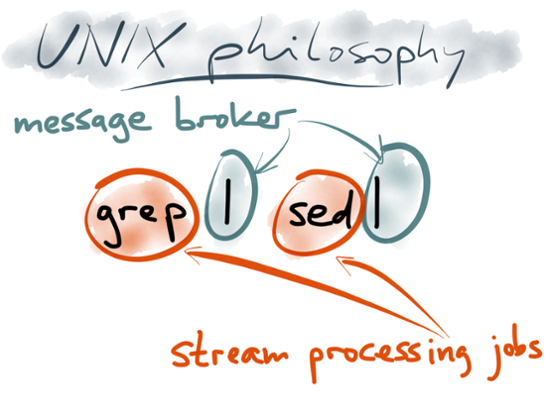

In fact, when you look at it through the Unix lens, Kafka looks quite like the pipe that connects the output of one process to the input of another. And Samza looks quite like a standard library that helps you read stdin and write stdout (and a few helpful additions, such as a deployment mechanism, state management, metrics, and monitoring). The style of stream processing jobs that you can write with Kafka and Samza closely follows the Unix tradition of small, composable tools:

In fact, when you look at it through the Unix lens, Kafka looks quite like the pipe that connects the output of one process to the input of another. And Samza looks quite like a standard library that helps you read stdin and write stdout (and a few helpful additions, such as a deployment mechanism, state management, metrics, and monitoring). The style of stream processing jobs that you can write with Kafka and Samza closely follows the Unix tradition of small, composable tools:

- In Unix, the operating system kernel provides the pipe, a transport mechanism for getting a stream of bytes from one process to another.

- In stream processing, Kafka provides publish-subscribe streams, a transport mechanism for getting messages from one stream processing job to another.

Kafka addresses the downsides of Unix pipes that we discussed previously:

- The single-machine limitation is lifted: Kafka itself is distributed by default, and any stream processors that use it can also be distributed across multiple machines.

- A Unix pipe connects exactly one process output with exactly one process input, whereas a stream in Kafka can have many producers and many consumers. Many inputs is important for services that are distributed across multiple machines, and many outputs makes Kafka more like a broadcast channel. This is very useful, since it allows the same data stream to be consumed independently for several different purposes (including monitoring and audit purposes, which are often outside of the application itself). Kafka consumers can come and go without affecting other consumers.

- Kafka also provides good fault tolerance: data is replicated across multiple Kafka nodes, so if one node fails, another node can automatically take over. If a stream processor node fails and is restarted, it can resume processing at its last checkpoint.

- Rather than a stream of bytes, Kafka provides a stream of messages, which saves the first step of input parsing (breaking the stream of bytes into a sequence of records). Each message is just an array of bytes, so you can use your favourite serialisation format for individual messages: JSON, XML, Avro, Thrift or Protocol Buffers are all reasonable choices. It’s well worth standardising on one encoding, and Confluent provides particularly good schema management support for Avro. This allows applications to work with objects that have meaningful field names, and not have to worry about input parsing or output escaping. It also provides good support for schema evolution without breaking compatibility.

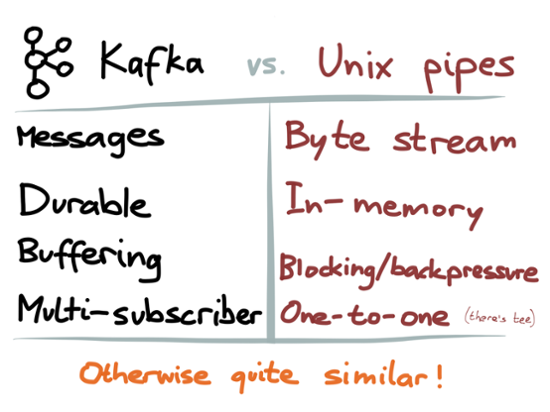

There are a few more things that Kafka does differently from Unix pipes, which are worth calling out briefly:

- As mentioned, Unix pipes provide a byte stream, whereas Kafka provides a stream of messages. This is especially important if several processes are concurrently writing to the same stream: in a byte stream, the bytes from different writers can be interleaved, leading to an unparseable mess. Since messages are coarser-grained and self-contained, they can be safely interleaved, making it safe for multiple processes to concurrently write to the same stream.

- Unix pipes are just a small in-memory buffer, whereas Kafka durably writes all messages to disk. In this regard, Kafka is less like a pipe, and more like one process writing to a temporary file, while several other processes continuously read that file using tail -f (each consumer tails the file independently). Kafka’s approach provides better fault tolerance, since it allows a consumer to fail and restart without skipping messages. Kafka automatically splits those ‘temporary’ files into segments and garbage-collects old segments on a configurable schedule.

- In Unix, if the consuming process of a pipe is slow to read the data, the buffer fills up and the sending process is blocked from writing to the pipe. This is a kind of backpressure. In Kafka, the producer and consumer are more decoupled: a slow consumer has its input buffered, so it doesn’t slow down the producer or other consumers. As long as the buffer fits within Kafka’s available disk space, the slow consumer can catch up later. This makes the system less sensitive to individual slow components, and more robust overall.

- A data stream in Kafka is called a topic, and you can refer to it by name (which makes it more like a Unix named pipe. A pipeline of Unix programs is usually started all at once, so the pipes normally don’t need explicit names. On the other hand, a long-running application usually has bits added, removed or replaced gradually over time, so you need names in order to tell the system what you want to connect to. Naming also helps with discovery and management.

Despite those differences, I still think it makes sense to think of Kafka as Unix pipes for distributed data. For example, one thing they have in common is that Kafka keeps messages in a fixed order (like Unix pipes, which keep the byte stream in a fixed order). This is a very useful property for event log data: the order in which things happened is often meaningful and needs to be preserved. Other types of message broker, like AMQP and JMS, do not have this ordering property.

So we’ve got Unix tools and stream processors that look quite similar. Both read some input stream, modify or transform it in some way, and produce an output stream that is somehow derived from the input. Importantly, the processing does not modify the input itself: it remains immutable. If you run awk on some input file, the file remains unmodified (unless you explicitly choose to overwrite it). Also, most Unix tools are deterministic, i.e. if you give them the same input, they always produce the same output. This means you can re-run the same command as many times as you want, and gradually iterate your way towards a working program. It’s great for experimentation, because you can always go back to your original data if you mess up the processing. This deterministic and side-effect-free processing looks a lot like functional programming. That doesn’t mean you have to use a functional programming language like Haskell (although you’re welcome to do so if you want), but you still get many of the benefits of functional code.

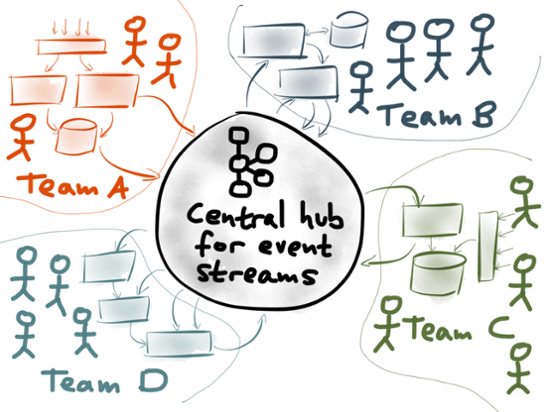

The Unix-like design principles of Kafka enable building composable systems at a large scale. In a large organisation, different teams can each publish their data to Kafka. Each team can independently develop and maintain stream processing jobs that consume streams and produce new streams. Since a stream can have any number of independent consumers, no coordination is required to set up a new consumer. We’ve been calling this idea a stream data platform. In this kind of architecture, the data streams in Kafka act as the communication channel between different teams’ systems. Each team focusses on making their particular part of the system do one thing well. While Unix tools can be composed to accomplish a data processing task, distributed streaming systems can be composed to comprise the entire operation of a large organisation. A Unixy approach manages the complexity of a large system by encouraging loose coupling: thanks to the uniform interface of streams, different components can be developed and deployed independently. Thanks to the fault tolerance and buffering of the pipe (Kafka), when a problem occurs in one part of the system, it remains localised. And schema management allows changes to data structures to be made safely, so that each team can move fast without breaking things for other teams.

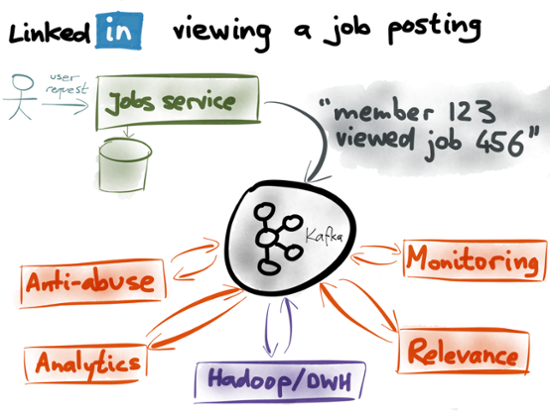

To wrap up this post, let’s consider a real-life example of how this works at LinkedIn. As you may know, companies can post their job openings on LinkedIn, and jobseekers can browse and apply for those jobs. What happens if a LinkedIn member (user) views one of those job postings? It’s very useful to know who has looked at which jobs, so the service that handles job views publishes an event to Kafka, saying something like “member 123 viewed job 456 at time 789”. Now that this information is in Kafka, it can be used for many good purposes:

- Monitoring systems: Companies pay LinkedIn to post their job openings, so it’s important that the site is working correctly. If the rate of job views drops unexpectedly, alarms should go off, because it indicates a problem that needs to be investigated.

- Relevance and recommendations: It’s annoying for users to see the same thing over and over again, so it’s good to track how many times the users has seen a job posting, and feed that into the scoring process. Keeping track of who viewed what also allows for collaborative filtering recommendations (people who viewed X also viewed Y).

- Preventing abuse: LinkedIn doesn’t want people to be able to scrape all the jobs, submit spam, or otherwise violate the terms of service. Knowing who is doing what is the first step towards detecting and blocking abuse.

- Job poster analytics: The companies who post their job openings want to see stats (in the style of Google Analytics) about who is viewing their postings, for example so that they can test which wording attracts the best candidates.

- Import into Hadoop and Data Warehouse: For LinkedIn’s internal business analytics, for senior management’s dashboards, for crunching numbers that are reported to Wall Street, for evaluating A/B tests, and so on.

All of those systems are complex in their own right, and are maintained by different teams. Kafka provides a fault-tolerant, scalable implementation of a pipe. A stream data platform based on Kafka allows all of these various systems to be developed independently, and to be connected and composed in a robust way. If you enjoyed this post, you’ll love my book Designing Data-Intensive Applications, published by O’Reilly. Thank you to Jay Kreps, Gwen Shapira, Michael Noll, Ewen Cheslack-Postava, Jason Gustafson, and Jeff Hartley for feedback on a draft of this post, and thanks also to Jay for providing the LinkedIn job view example.

Avez-vous aimé cet article de blog ? Partagez-le !

Abonnez-vous au blog Confluent

How a Tier‑1 Bank Tuned Apache Kafka® for Ultra‑Low‑Latency Trading

A global investment bank and Confluent used Apache Kafka to deliver sub-5ms p99 end-to-end latency with strict durability. Through disciplined architecture, monitoring, and tuning, they scaled from 100k to 1.6M msgs/s (<5KB), preserving order and transparent tail latency.

How to Build a Custom Kafka Connector – A Comprehensive Guide

Learn how to build a custom Kafka connector, which is an essential skill for anyone working with Apache Kafka® in real-time data streaming environments with a wide variety of data sources and sinks.