[Webinar] From Fire Drills to Zero-Loss Resilience | Register Now

Flink vs Kafka: a Complete Comparison

This blog post is written jointly by Stephan Ewen, CTO of data Artisans, and Neha Narkhede, CTO of Confluent. Stephan Ewen is PMC member of Apache Flink and co-founder and CTO of data Artisans. Before founding data Artisans, Stephan was leading the development that led to the creation of Apache Flink. Stephan holds a PhD. in Computer Science from TU Berlin. You can also find this post on the data Artisans blog.

The open source stream processing space is exploding, with more streaming platforms available than ever. presenting users with many alternatives. In the Apache Software Foundation alone, there are now over 10 stream processing projects, some in incubation and others graduated to top-level project status. While the availability of alternatives benefits users and the industry as a whole by enabling competition and thus, encouraging innovation, it can also be quite confusing: with all these options, which is the best stream processing system for me now, and in the future? Stream processors can be evaluated on several dimensions, including performance (throughput and latency), integration with other systems, ease of use, fault tolerance guarantees, etc, but making such a comparison is not the topic of its post (and we are certainly biased).

For some time now, the Apache Kafka project has served as a common denominator in most open source stream processors as the the de-facto storage layer for storing and moving potentially large volumes of streaming data with low latency. Recently, the Kafka community introduced Kafka Streams, a stream processing library that ships as part of Apache Kafka. With the addition of Kafka Streams and Kafka Connect, Kafka has now added significant stream processing capabilities.

In this post, we focus on discussing how Flink and Kafka Streams compare with each other on stream processing, and we attempt to provide clarity on that question in this post. Flink and Kafka Streams were created with different use cases in mind. While they have some overlap in their applicability, they are designed to solve orthogonal problems and have very different sweet spots and placement in the data infrastructure stack.

First, let’s look into a quick introduction to Flink and Kafka Streams.

What is Apache Flink?

Apache Flink’s roots are in high-performance cluster computing, and data processing frameworks. Flink runs self-contained streaming computations that can be deployed on resources provided by a resource manager like YARN, Mesos, or Kubernetes. Flink jobs consume streams and produce data into streams, databases, or the stream processor itself. Flink is commonly used with Kafka as the underlying storage layer, but is independent of it.

Before Flink, users of stream processing frameworks had to make hard choices and trade off either latency, throughput, or result accuracy. Flink was the first open source framework (and still the only one), that has been demonstrated to deliver (1) throughput in the order of tens of millions of events per second in moderate clusters, (2) sub-second latency that can be as low as few 10s of milliseconds, (3) guaranteed exactly once semantics for application state, as well as exactly once end-to-end delivery with supported sources and sinks (e.g., pipelines from Kafka to Flink to HDFS or Cassandra), and (4) accurate results in the presence of out of order data arrival through its support for event time. Flink is based on a cluster architecture with master and worker nodes. Flink clusters are highly available, and can be deployed standalone or with resource managers such as YARN and Mesos. This architecture is what allows Flink to use a lightweight checkpointing mechanism to guarantee exactly-once results in the case of failures, as well allow easy and correct re-processing via savepoints without sacrificing latency or throughput. Finally, Flink is also a full-fledged batch processing framework, and, in addition to its DataStream and DataSet APIs (for stream and batch processing respectively), offers a variety of higher-level APIs and libraries, such as CEP (for Complex Event Processing), SQL and Table (for structured streams and tables), FlinkML (for Machine Learning), and Gelly (for graph processing). Flink has been proven to run very robustly in production at very large scale by several companies, powering applications that are used every day by end customers.

What is the Kafka Streams API?

In contrast, the Streams API is a powerful, embeddable stream processing engine for building standard Java applications for stream processing in a simple manner. Such Java applications are particularly well-suited, for example, to build reactive and stateful applications, microservices, and event-driven systems. As a native component of Apache Kafka since version 0.10, the Streams API is an out-of-the-box stream processing solution that builds on top of the battle-tested foundation of Kafka to make these stream processing applications highly scalable, elastic, fault-tolerant, distributed, and simple to build. The gap the Streams API fills is less the analytics-focused domain and more building core applications and microservices that process data streams.

The goal of the Streams API is to simplify stream processing enough to make it accessible as a mainstream application programming model. To aid in that goal, there are a few deliberate design decisions made in the Streams API — 1) It is an embeddable library with no cluster, just Kafka and your application. With the Streams API you can focus on building applications that drive your business rather than on building clusters. This makes it significantly more approachable to application developers looking to do stream processing, as it seamlessly integrates with a company’s existing packaging, deployment, monitoring and operations tooling 2) It is fully integrated with core abstractions in Kafka, so all the strengths of Kafka — failover, elasticity, fault-tolerance, scalability and security — are available and built-in to the Streams API; Kafka is battle-tested and is deployed at scale in thousands of companies worldwide, allowing the Streams API to build on that strong foundation 3) It introduces new concepts and functionality to allow for stream processing, such as fully integrating the abstractions of streams and of tables, which you can use interchangeably within your application to achieve, for example, highly performant join operations and continuous queries.

Flink vs Kafka Streams API: Major Differences

The table below lists the most important differences between Kafka and Flink:

| Apache Flink | Kafka Streams API | |

| Deployment | Flink is a cluster framework, which means that the framework takes care of deploying the application, either in standalone Flink clusters, or using YARN, Mesos, or containers (Docker, Kubernetes) | The Streams API is a library that any standard Java application can embed and hence does not attempt to dictate a deployment method; you can thus deploy applications with essentially any deployment technology — including but not limited to: containers (Docker, Kubernetes), resource managers (Mesos, YARN), deployment automation (Puppet, Chef, Ansible), and custom in-house tools. |

| Life cycle | User’s stream processing code is deployed and run as a job in the Flink cluster | User’s stream processing code runs inside their application |

| Typically owned by | Data infrastructure or BI team | Line of business team that manages the respective application |

| Coordination | Flink Master (JobManager), part of the streaming program |

Leverages the Kafka cluster for coordination, load balancing, and fault-tolerance. |

| Source of continuous data | Kafka, File Systems, other message queues | Strictly Kafka with the Connect API in Kafka serving to address the data into, data out of Kafka problem |

| Sink for results | Kafka, other MQs, file system, analytical database, key/value stores, stream processor state, and other external systems | Kafka, application state, operational database or any external system |

| Bounded and unbounded data streams | Unbounded and Bounded | Unbounded |

| Semantical Guarantees | Exactly once for internal Flink state; end-to-end exactly once with selected sources and sinks (e.g., Kafka to Flink to HDFS); at least once when Kafka is used as a sink, is likely to be exactly-once end-to-end with Kafka in the future | Exactly-once end-to-end with Kafka |

The fundamental differences between a Flink and a Streams API program lie in the way these are deployed and managed (which often has implications to who owns these applications from an organizational perspective) and how the parallel processing (including fault tolerance) is coordinated. These are core differences – they are ingrained in the architecture of these two systems.

Deployment and Organizational Management

A Flink streaming program is modeled as an independent stream processing computation and is typically known as a job. The entire lifecycle of a Flink job is the responsibility of the Flink framework; be it deployment, fault-tolerance or upgrades. The resources used by a Flink job come from resource managers like YARN, Mesos, pools of deployed Docker containers in existing clusters (e.g., a Hadoop cluster in case of YARN), or from standalone Flink installations. Flink jobs can start and stop themselves, which is important for finite streaming jobs or batch jobs. From an ownership perspective, a Flink job is often the responsibility of the team that owns the cluster that the framework runs, often the data infrastructure, BI or ETL team.

The Streams API in Kafka is a library that can be embedded inside any standard Java application. As such, the lifecycle of a Kafka Streams API application is the responsibility of the application developer or operator. The Streams API does not dictate how the application should be configured, monitored or deployed and seamlessly integrates with a company’s existing packaging, deployment, monitoring and operations tooling. From an ownership perspective, a Streams application is often the responsibility of the respective product teams.

Besides affecting the deployment model, running the stream processing computation embedded inside your application vs. as an independent process in a cluster touches issues like resource isolation or separation vs. unification of concerns. For instance, running a stream processing computation inside your application means that it uses the packaging and deployment model of the application itself. And running a stream processing computation on a central cluster means that you can allow it to be managed centrally and use the packaging and deployment model already offered by the cluster. Likewise, running a stream processing computation on a central cluster provides separation of concerns as the stream processing part of the application’s business logic lives separately from the rest of the application and the message transport layer (for example, this means that resources dedicated to stream processes are isolated from resources dedicated to Kafka). On the other hand, running a stream processing computation inside your application is convenient if you want to manage your entire application, along with the stream processing part, using a uniform set of operational tooling. Depending on the requirements of a specific application, one or the other approach may be more suitable.

Call out: Stream processing is used in a variety of places in an organization — from user-facing applications to running analytics on streaming data. The Streams API in Kafka and Flink are used in both capacities. The main distinction lies in where these applications live — as jobs in a central cluster (Flink), or inside microservices (Streams API).

Distributed Coordination and Fault Tolerance

The biggest difference between the two systems with respect to distributed coordination is that Flink has a dedicated master node for coordination, while the Streams API relies on the Kafka broker for distributed coordination and fault tolerance, via the Kafka’s consumer group protocol. While this sounds like a subtle difference at first, the implications are quite significant.

In Apache Flink, fault tolerance, scaling, and even distribution of state are globally coordinated by the dedicated master node. Flink’s master node implements its own high availability mechanism based on ZooKeeper. A failure of one node (or one operator) frequently triggers recovery actions in other operators as well (such as rolling back changes). This approach helps Flink to get its high throughput with exactly once guarantees, it enables Flink’s savepoint feature (for application snapshots and program and framework upgrades), and it powers Flink’s exactly-once sinks (e.g., HDFS and Cassandra, but not Kafka). Even for nondeterministic programs, Flink can that way guarantee results that are equivalent to a valid failure-free execution. It is worth pointing out that since Kafka does not provide an exactly-once producer yet, Flink when used with Kafka as a sink does not provide end to end exactly-once guarantees as a result.

The Streams API in Kafka provides fault-tolerance, guarantees continuous processing and high availability by leveraging core primitives in Kafka. Each shard or instance of the user’s application or microservice acts independently. All coordination is done by the Kafka brokers; the individual application instances simply receive callbacks to either pick up additional partitions (scale up) or to relinquish partitions (scale down). Fault tolerance is built-in to the Kafka protocol; if an application instance dies or a new one is started, it automatically receives a new set of partitions from the brokers to manage and process. The application that embeds the Streams API program does not have to integrate with any special fault tolerance APIs or even be aware of the fault tolerance model. This allows for a very lightweight integration; any standard Java application can use the Streams API.

To summarize, while the global coordination model is powerful for streaming jobs in Flink, it works less well for standalone applications and microservices that need to do stream processing: the application would have to participate in Flink’s checkpointing (implement some APIs) and would need to participate in the recovery of other failed shards by rolling back certain state changes to maintain consistency. That is clearly not as lightweight as the Streams API approach. Again, both approaches show their strength in different scenarios.

Conclusion

In summary, while there certainly is an overlap between the Streams API in Kafka and Flink, they live in different parts of a company, largely due to differences in their architecture and thus we see them as complementary systems. The Streams API makes stream processing accessible as an application programming model, that applications built as microservices can avail from, and benefits from Kafka’s core competency —performance, scalability, security, reliability and soon, end-to-end exactly-once — due to its tight integration with core abstractions in Kafka. Flink, on the other hand, is a great fit for applications that are deployed in existing clusters and benefit from throughput, latency, event time semantics, savepoints and operational features, exactly-once guarantees for application state, end-to-end exactly-once guarantees (except when used with Kafka as a sink today), and batch processing.

Finally, Flink and core Kafka (the message transport layer) are of course complementary, and together are a great fit for a streaming architecture. The data Artisans and Confluent teams remain committed to guaranteeing that Flink and Kafka work great together in all subsequent releases of the frameworks.

Try out Kafka’s Streams API

If you have enjoyed this article, you might want to continue with the following resources to learn more about Apache Kafka’s Streams API:

- Get started with the Kafka Streams API to build your own real-time applications and microservices.

- Walk through our Confluent tutorial for the Kafka Streams API with Docker and play with our Confluent demo applications.

Avez-vous aimé cet article de blog ? Partagez-le !

Abonnez-vous au blog Confluent

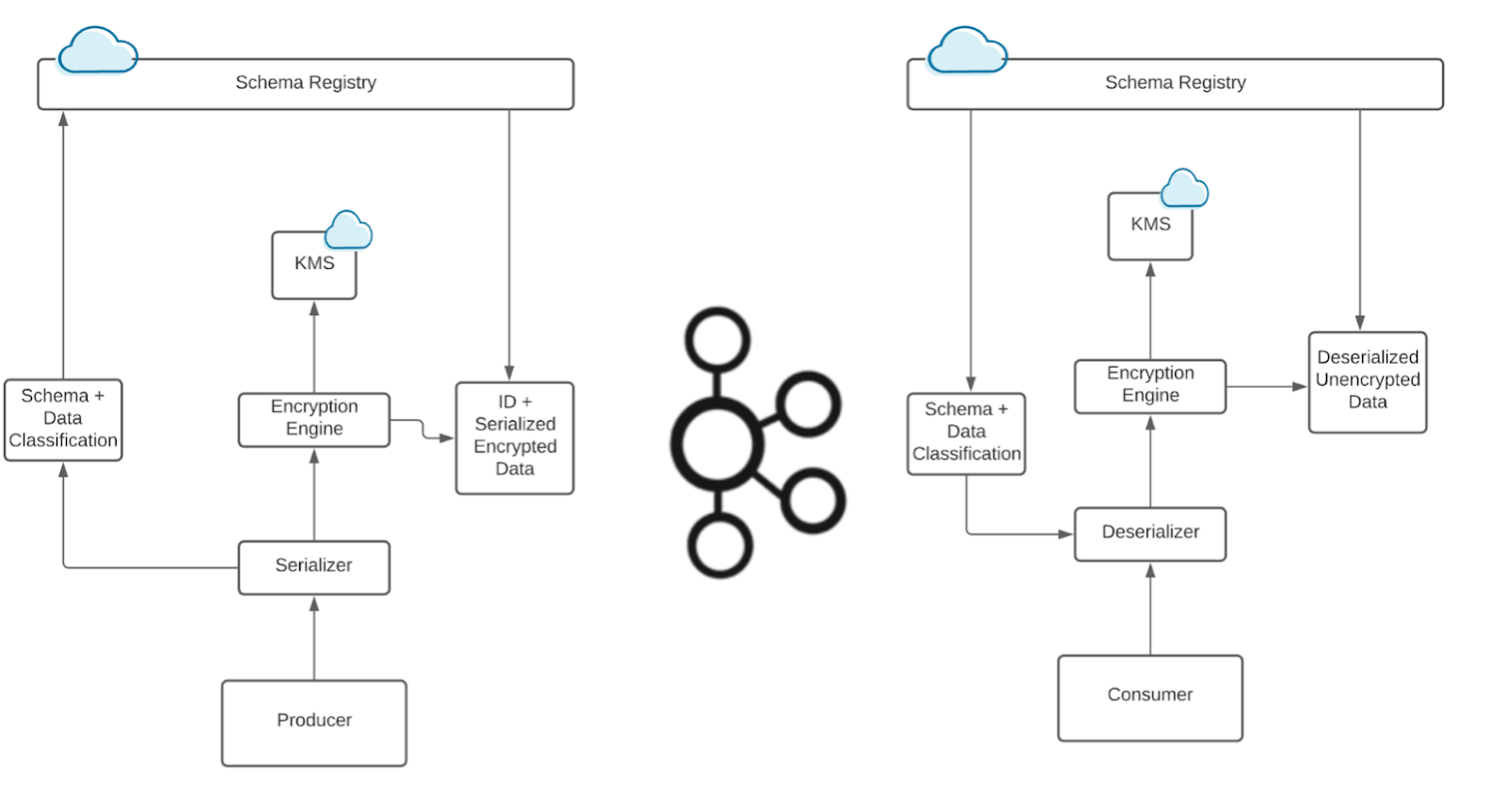

How to Protect PII in Apache Kafka® With Schema Registry and Data Contracts

Protect sensitive data with Data Contracts using Confluent Schema Registry.

Confluent Deepens India Commitment With Major Expansion on Jio Cloud

Confluent Cloud is expanding on Jio Cloud in India. New features include Public and Private Link networking, the new Jio India Central region for multi-region resilience, and streamlined procurement via Azure Marketplace. These features empower Indian businesses with high-performance data streaming.